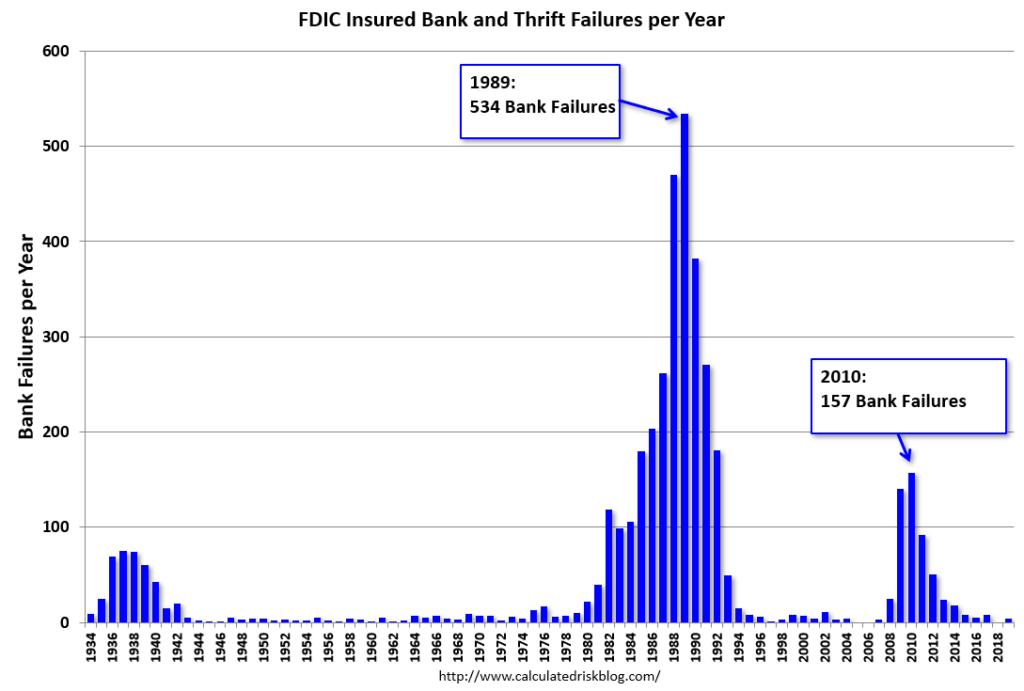

One of the best economics blogs out there, Calculated Risk, recently published this excellent chart:

What we’re looking at here is the total number of bank failures per year among FDIC insured depositories (which, in the U.S., effectively means all banks, credit unions and, once upon a time, savings and loans). The spike in the 1930s is an obvious post-market crash Great Depression event, while the 1980s failures was kicked off with a big recession in the early 1980s and exacerbated by the Savings and Loan crisis which is a largely forgotten chapter in American financial history. The cause of the late 2000’s spike is much more well known nowadays: the subprime mortgage crisis and Great Recession.

This chart is instructive in that it shows that the bank failures in the 2000s, while a big spike from before, were actually modest when compared to the 1980s disaster and, if adjusted for population size, small compared to the 1930s crisis as well. Those of us who lived through the crisis and remember it clearly find it hard to discount it as one of the lesser bank disasters in American history, but that appears to be the case.

What drove those bank failures? That is a complex topic, but it ultimately is a story of leverage and regulation. Banks have limits on what kind of assets they can hold, and how much of different asset types they can put against their debts. If the ratio between the two goes above regulatory restrictions, the bank needs to offload debts, acquire assets, or face failure. Post-2008, none of that was easy to do. And so banks had to shut down.

After spiking in 2010, the bank failures quickly declined as markets began to recover and the worst banks had already vanished or been saved by other banks acquiring their businesses, causing a collapse in total bank failures over the last six years. In 2019, just four banks failed, below the median 7 from 1933, when the FDIC was established.

Bank failures are an important topic not so much because of what they say about the economy or as a leading indicator (they very much lag the trend), but because of how information like this is often used to manipulate investor sentiment. Throughout the early 2010s, the spike in bank failures was a popular talking point among doom-and-gloom prognosticators, despite the rather obvious fact that these failures are a symptom of a disease that’s already come and gone rather than a harbinger of doom.

For bankers, bank failures are a valuable case study in how risk and capital management can fail, and what causes their failures. By understanding both the regulatory and market driven dynamics that cause bank failures, bankers can help to manage risk and keep their own bank from becoming a statistic.