Stockpicking is definitely the most famous part of high finance, but it’s also the smallest. Bond markets are bigger, debt financing is more lucrative, and optimizing firm capital structure is where the best financiers can make the biggest impact in a company’s future.

Finance students will learn about the capital structure in class, but often the complex calculations used to compare different assets obscures the simple elegance and logic behind the capital structure. Understanding this logic on an intuitive level makes working in finance easier and more enjoyable.

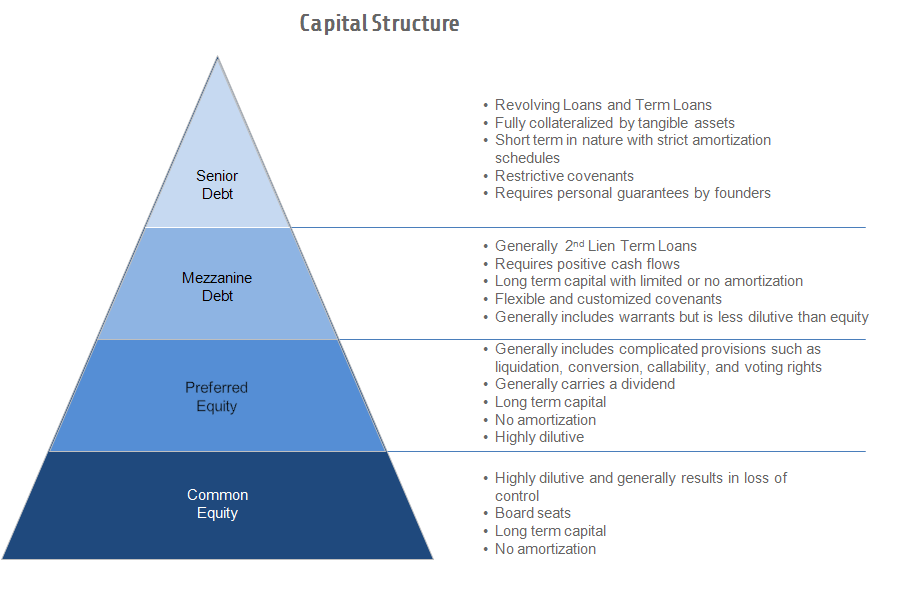

So what is the capital structure? Think of it as a pyramid.

In the pyramid, you have the most senior debt at the top and the most junior equity at the bottom. Debt is always above equity.

“Senior” simply refers to preferential treatment in liquidation. When a company is operating, it’s up to the chief financial officer to ensure everyone holding assets in the capital structure get their payouts and cash flows go to where they should go. It’s like an air traffic controller ensuring that the flow of movement of different parts continues peacefully, and everyone ends up at their destination.

But when a company goes bankrupt, everything must turn into cash—i.e., everything must liquidate. When this happens, the market value of each asset must be exchanged for cash, and any outstanding payments must be given to those asset holders as per the contractural agreements that are behind them.

In this case, there may not be enough cash to go around, which is why the capital structure is so important. Those things at the top—the senior assets—will get liquidated first. If there’s enough cash left over after liquidating senior debts (i.e., paying them and outstanding interest payments back), mezzanine debt gets paid off. If they get paid off, you go to preferred equity (in many corporations, there are bonds between mezzanine debt and preferred equity). Then you go to common equity—if there’s any left over.

This is why in bankruptcies the common stock of a company will go to near zero. Rarely is there enough cash left over to give shareholders any cash. That’s why this is the riskiest part of the capital structure—and why investing in diversified stocks isn’t as safe as many assume.

It’s also why financial professionals diversify across the capital structure—buying preferred stocks, corporate bonds, and senior loans when necessary. Ideally, a diversified portfolio will have bond holdings in the riskiest companies and equity holdings in safer companies. Thus risk is spread out, exposure to bankruptcies is minimized, and the portfolio still has the potential for large returns if the riskier companies turn out to be big winners.

Doing that in a winning formula that can beat the S&P 500, however, isn’t easy. But it isn’t impossible—and it’s where portfolio managers really shine.